Josephine S F CHOW,1-5* Louise COLLINGRIDGE, 1,2,6 Jacqueline RAMIREZ,1,2, Janine BYRNE,7 Allyson CALVIN,8 Glenda RAYMENT,9 Rosemary SIMMONDS,10 Nadine TINSLEY11

1South Western Sydney Nursing & Midwifery Research Alliance, South Western Sydney Local Health District, New South Wales

2Ingham Institute for Applied Medical Research, Liverpool, New South Wales

3Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales

4NICM Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, New South Wales

5Faculty of Nursing, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Tasmania

6Qualitative Research Consultant, Sydney, New South Wales

7Home Haemodialysis Unit, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Woolloongabba, Queensland

8Renal Unit, Canberra Hospital, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory

9Renal Unit, Liverpool Hospital, Liverpool, New South Wales

10Department of Renal Medicine, Barwon Health, Geelong, Victoria

11Top End Renal Service, Larrakeyah, Northern Territory

*Corresponding Author: Josephine S F CHOW, South Western Sydney Nursing & Midwifery Research Alliance, South Western Sydney Local Health District, New South Wales.

Received Date: March 15, 2024

Accepted Date: March 20, 2024

Published Date: March 25, 2024

Citation: Josephine S F CHOW, Louise COLLINGRIDGE, Jacqueline RAMIREZ, Janine BYRNE, Allyson CALVIN et al. (2024) “Constructing Adherence: Nursing Perspectives on Home Dialysis.”, Clinical Case Reports and Clinical Study, 11(1); DOI: 10.61148/2766-8614/JCCRCS/173

Copyright: © 2024 Josephine S F CHOW. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Aims

Dialysis (frequency and length) and measures of health function are usually associated with adherence for in-patient services for patients with kidney failure. Adherence expectations specific to home dialysis are not reported in the literature. Home dialysis offers autonomy and flexibility for patients, whilst at the same time is closely monitored by specialist nurses.

A preliminary qualitative investigation was conducted to understand how renal nurse practitioners construct adherence for patients undergoing home dialysis.

Semi structured interviews were recorded, transcribed and analysed following principles of thematic analysis. Thematic analysis indicated that markers of adherence were biological or behavioural. Factors contributing to non-adherence were mental health, social, health, and system related. Adherence was found to be dynamic, and decisions about when to intervene were reported as individually determined. The patient/nurse relationship was found to be integral to notions of adherence in home dialysis. The nurses’ role was seen to be evolving and responsive. Further investigations of converging patient and nursing constructions of adherence are needed to determine if these preliminary findings are an indication that policies and procedures should recognize adherence as dynamic and grounded in the nurse-patient relationship.

Introduction

Patients with kidney failure (KF) face life changing dialysis treatments at home, at satellite clinics or in hospital that are monitored by renal specialists [1]. Early studies found low adherence in both haemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients ([see for example 2]). Adherence indicators for dialyisis were initially used for in hospital HD monitoring, and primarily refer to treatment schedules (missed or shortened dialysis sessions), health targets (weight, phosphorous levels), or dietary and fluid intake guidelines [1]. Non-adherent in-hospital dialysis patients are understood to miss one or more HD sessions per month, shorten treatment sessions by 10 minutes or more, record interdialytic weight gain greater than 5.7 % of dry weight, or record Phosphorus greater than 6.5 mg/dL [3]. Missing medications, smoking, or avoiding requested medical investigations may also be considered non-adherence for patients undergoing dialysis[2]. Increasing adherence has been attempted by a range of approaches, such as family support [4], remote patient monitoring [5], computer or online applications for monitoring [6], Cognitive Behavioural Therapy [7], education [8], and reliance on the experience of nurses [9]. Home dialysis aims to increase adherence by offering flexibility and autonomy for patients. When undertaking treatment at home, patients need to self monitor [10]. Nonetheless, nurses also closely monitor patients undertaking dialysis at home [11]. Patients thus benefit from a clear understanding of what is required of them to meet adherence standards set by the nurses monitoring their treatment [12].

Although markers of adherence to dialysis are, as outlined above, typically health and treatment measures, adherence to treatment for chronic health conditions is widely recognized as being determined by both medical and non-medical factors such as the healthcare system, patient factors and disease condition [13]. This study, a precursor to studies of understanding of adherence by patients being treated for KF, investigates how nurses construct adherence in patients undergoing home dialysis. A qualitative methodology was adopted to capture possible complexity resulting from a prescribed and closely monitored treatment schedule, conversely offered with a degree of flexibility and patient autonomy.

Methods

The construction of adherence by nurses applied to home dialysis was investigated. The method of reflexive thematic analysis [14] was utilised, embedded in a social constructivist approach [15] incorporating ethnographic principles [16]. Semi-structured interviews with participants were conducted by an outsider researcher, audio-recorded and then transcribed verbatim. Supplementary documentation used by interviewees such as templates for contracts with patients or policy statements was collected, if available. Summaries of each individual interviewee’s account, integrated with any documentation they had supplied were produced. Thematic analysis of the summaries, with cross reference to interview transcripts, followed the practical steps of familiarization with the data, coding, searching for themes, reviewing themes, searching and naming themes and writing [17].

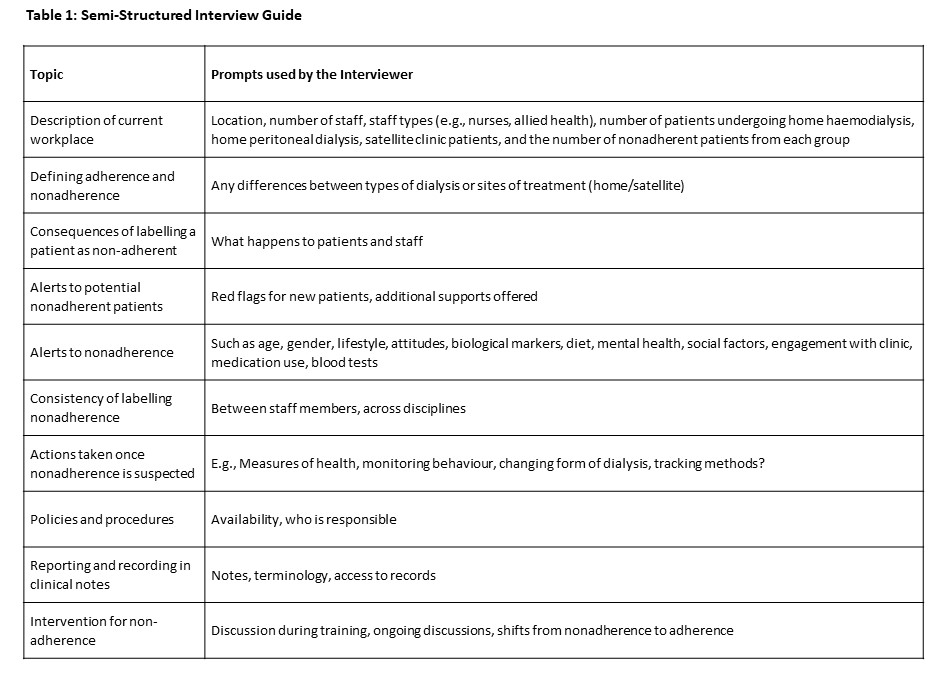

An interview guide (see Table 1) was developed by the researchers. The guide was used as a prompt by the interviewer during each semi-structured interview. Topics were designed to firstly elicit context from a description of the clinic that each was currently working in. Subsequent topics and probing questions were designed to elicit perspectives on non-adherence in home dialysis. Participants were asked if documentation was available to support decision making. If such documentation was available, participants were invited to send de-identified copies to the interviewer. Documents supplied by participants provided background reading for the researcher who analysed and interpreted the data. To ensure rigor and transparency, the principles of the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) were adopted [18]. COREQ principles provided the researchers with guidelines to ensure accountability in the qualitative research method adopted.

Participants

Renal nurse practitioners in Australia are appointed to monitor and support patients with KF, including undertaking laboratory reviews, medication reviews, managing prescriptions, patient reviews, and referrals [19]. Renal nurse practitioners are involved in training for patients who undertake home dialysis. Participants in this study were renal nurse practitioners with experience of supporting home patients. They were responsible for patients attached to renal dialysis centres across Australia. Participants were also members of The HOME Network (THN). Established in 2010, THN brings together healthcare professionals in the field of home dialysis with the aim of identifying and addressing barriers to optimal utilisation of home dialysis in Australia [20]. All THN members who were also renal nurse practitioners supporting patients on dialysis were invited to participate. A total of fourteen potential participants met those criteria.

Participation was strictly voluntary, and all participants were required to provide consent prior to interviews.

All identified potential participants received an emailed invitation package from the Principal Investigator. The invitation included a participant information sheet, an offer to participate and a consent form. Invited participants were asked to contact an independent qualitative researcher (not a member of THN and with no connection to dialysis units) if they consented to participate in the study.

All further handling of any potentially identifying information (including signed consent forms, interview schedule and recordings of interviews before deidentification) was managed by the independent researcher. Materials were only shared with other researchers after being transcribed and deidentified.

Data collection

The interview guideline (Table 1) developed by the study investigators was designed to address the research question of how adherence is constructed by nurses supporting those undergoing home dialysis. Topics were introduced by the interviewer, and probing questions used as required. A general description of the service and adherence to treatment was asked for first, to provide context. A combination of closed and open-ended questions was incorporated into the interview guideline to allow for comparison of findings across participants, as well as to identify issues that might emerge and might be unique to a particular experience.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted between November 2021 and June 2022. Interviews were conducted by either telephone or online, depending on internet access and facilities available to the participant. If recorded online, participants and the interviewer turned off cameras to ensure no visual identifiers were available on the recording. The interviewer recorded notes during interviews to assist with transcription and analysis. During each interview, participants were invited to share any supplementary documentation related to adherence such as policies and procedures. Supplementary material was emailed to the interviewer after the interview had concluded. No data was collected from hospital records.

Recordings of interviews were transcribed by a third party (JR) and checked by the interviewer (LC) against recordings. Participants were offered the option of reviewing the transcript of their interview. Three participants requested to see their transcripts. None requested any deletion or correction to the transcripts. Integrating deidentified interview data from transcripts with supplementary documents supplied by the participants yielded nine individual case summaries (LC). The nine summaries served as the data from which themes were identified, with reference back to verbatim transcripts for clarification and extraction of examples of evidence.

Data Analysis

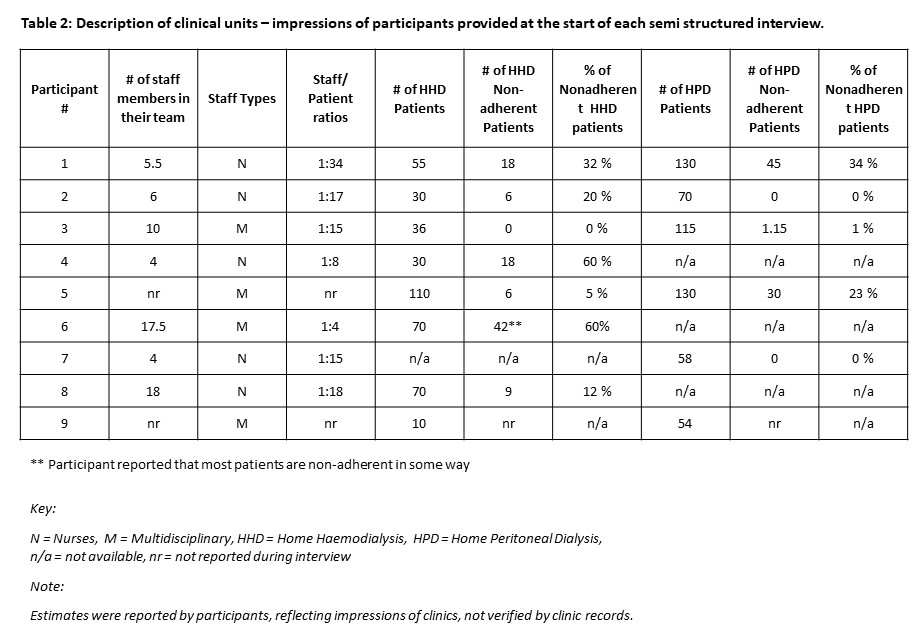

Case summaries and interview transcripts were read and reread by the independent researcher. Contextual information about each of the clinical units the participants were employed in were summarized in table form to show type of clinic (urban/regional/remote), staff to patient ratios, and estimated percentages of non-adherent patients, as perceived by each participant.

Content of the nine case summaries with cross reference to verbatim transcripts was progressively analysed using an inductive thematic analysis approach. Similarities and differences between participant responses were extracted and interpreted in relation to the context of their clinical unit. Themes were identified. Data analysis was led by the independent researcher (LC) who had conducted the interviews and research team (JSC & JR). All authors reviewed the transcripts and case summaries.

Findings

Nine semi-structured interviews (64% of all eligible participants) were conducted. Interviews were between 34 and 62 minutes in duration. All participants who accepted the invitation and provided consent were included in this study. Three main themes identified in the transcribed interviews were: service delivery context, markers of, and factors contributing to nonadherence, and interventions taken. The findings below are presented under these same headings.

The terms adherence and non-adherence were used by the interviewer. Participants either used the same terminology or referred to compliance and non-compliance, interchangeably with adherence/non-adherence. This variation in terminology is reflected in extracts from participants shown in the results below.

Service Delivery Context

To provide context at the start of each semi-structured interview, each participant was first asked to describe the clinic in which they worked (team make up,) the type of dialysis services their renal dialysis centre supported (home HD and/or home PD) and whether for urban, regional, or rural and remote [21] communities and their approximation of the number of patients undertaking each type of dialysis, and the proportion considered to be non-adherent. The answers to this first question from all participants are summarised in Table 2. The descriptions of clinics provided context for the interviewer. The answers indicated the scale of adherence the participants were referring to in subsequent questions. As shown in Table 2, most teams were described as multidisciplinary, although some were described as staffed by nurses only. Staff to patient ratios were reported as similar across most participants, but there were also extremes of high and low ratios. Of note was that for some services, participants reported high rates of adherence, and for others many patients were considered not to be adherent. This wide variation underscored the importance of further probing during interviews to gain a better understanding if adherence was differently constructed to yield such varied perceptions, or if the concept was similarly constructed, but other factors contributed to the perception of participants.

Participants provided services across urban, regional, and rural and remote areas. Treatment types included home Haemodialysis (HHD), Peritoneal Dialysis (PD) and in two of the nine cases, the same centre serviced satellite (facility-based) dialysis.

Of note, not shown on Table 2 to avoid possible identification, was that funding models varied as a function of the State/Territory in which the health service was delivered. Some dialysis centres were administered by private companies involved in supplying equipment for dialysis, whereas others were publicly funded as part of state-based healthcare, and others were a combination of private and public funding. Government policy was an influence on patient care but could not be commented on in detail in this paper without potentially identifying services or participants. Initial reading of transcripts indicated variations between accounts of participants in terms of the health service model and the reported proportion of non-adherence amongst the patients being treated. Due to the small number of participants and the reports of adherence being impressions of participants not verified by patient records, it was not possible to comment on any causal or other type of relationship between the service delivery model and adherence. However, what did emerge was that a home dialysis policy may be a government initiative, but observations by the specialist teams can override that decision where patients are deemed unsuitable. “our nephrology team talking medico and um leadership so high above um a very much for a home dialysis first model, but we don’t enforce that. So when I say that our nephrology team believe in home dialysis, but they won’t, they also believe in patient choice” (Participant #3).

Markers of, and factors contributing to non-adherence

Whether or not participants reported occurrences of non-adherence in their centres, vigilance about attending to markers of non-adherence was reported as an ongoing clinical process to allow for timely intervention if non-adherence should emerge. Non-adherence / adherence was described as a dynamic process that individuals experience, rather than as a fixed state.

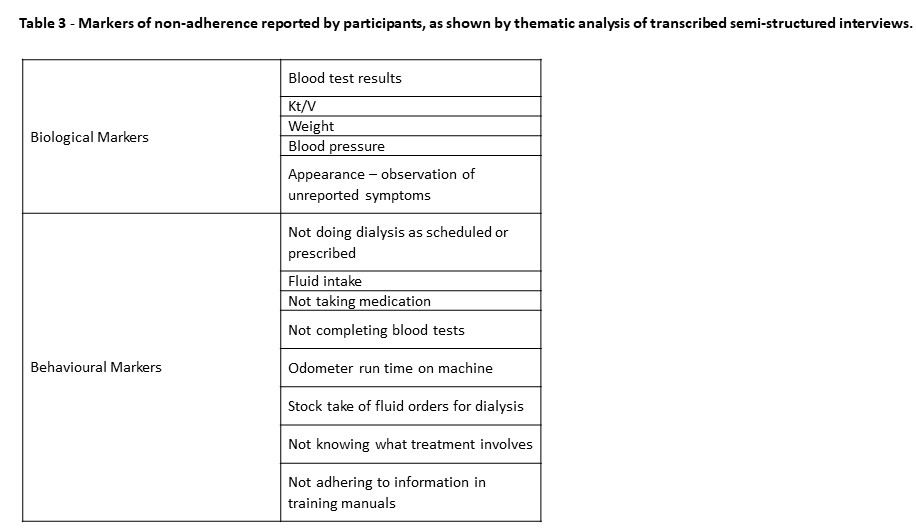

Markers of nonadherence were identified as biological or behavioural. Factors that might contribute to shifts between adherence and non-adherence were identified as mental health, social, health or system related. Participants described their ongoing role, as renal nurse practitioners, as monitoring and reviewing patients, whether they were deemed non-adherent at any given time. Most participants noted non-adherence was usually to schedules for collecting blood for regular testing, with non-adherence to the dialysis schedule being less common.

Participants reported being alerted to patients potentially becoming non-adherent during initial training “Ah, I think when you’re training when they don’t take advice. Um, they say “oh I like doing it this way”. That’s a little bit of a flag [mm], because um, they were in their primary stage um, they haven’t got that much knowledge yet, they’re telling you what that’s that’s the alert”. (Participant #4). Non-adherence is alerted to during training when attitudinal or behaviours issues such as not being willing or able to learn, risky lifestyle behaviours, lack of a support network, or financial / housing constraints. Behaviour and progress indicators during training were described as alerts to non-adherence including not taking advice during training, progress during learning and non-attendance at booked appointments during the training period were considered alerts. In some dialysis centres, home dialysis was offered despite early indicators of non-adherence risk. In others, a decision might be made whether to offer home dialysis or not.

Experienced nurses were both more alert to potential non-adherence “It’s a gut feeling, I say to the staff [ok] you know that patient’s not dialysing and they go “of course he is”, I go “no he’s not” and sure enough you know.” (Participant #2). Experienced nurses, in addition to recognising non-adherence, were reported as tolerating lapses in adherence more so than less experienced nurses. Social and personal circumstances known to nurses can account for when patients are not dialysing or not undertaking regular blood tests, and may be considered adherent or non-adherent “So they’ll [referring to new staff members] think they’re [certain patients] non-compliant but the rest of us know, no its not that they’re really non-compliant, it that’s they’re very very busy men or women and um and we sort of do special arrangements for them So you know they think they’re non-compliant, but know that’s not, we don’t see it as non-compliance.” (Participant # 2).

Participants described less experienced nurses as reacting to non-adherence more quickly than those with many years of experience working with patients with KF. The observation that nursing experience was a factor in recognising non-adherence provided further evidence for adherence being constructed from a complex interaction between patients and healthcare providers.

Shifts between adherence and non-adherence were reported to occur as factors affecting individual patients emerged over time. Markers of non-adherence provided by participants are listed in Table 3. Participants described markers that were biological or behavioural.

Unexpected or unexplained blood test results were understood to be a biological marker of non-adherence. ”what happens with our patients is its more um, it will be more the blood tests that will alert me” (Participant #2). No quantitative cut offs were reported to be used, but rather whenever the blood tests did not appear as expected, patients would be contacted for a review. Other health measures or observable symptoms were also reported as biological markers of non-adherence.

Behavioural markers were those that were controlled by what patients did. Not doing dialysis was reported as less common than not submitting for regular blood tests or taking medication. “So they, they’re just um, very comfortable with it and just um make it such as part of their life that they um, that they’re mainly non-adherent around getting their blood tests done.” (Participant #2). Fluid intake, whilst mentioned was less of a concern for home dialysis patients because patients can change the frequency or length of dialysis to compensate for a higher intake of fluids, an option that is not available to in hospital dialysis patients on fixed schedules.

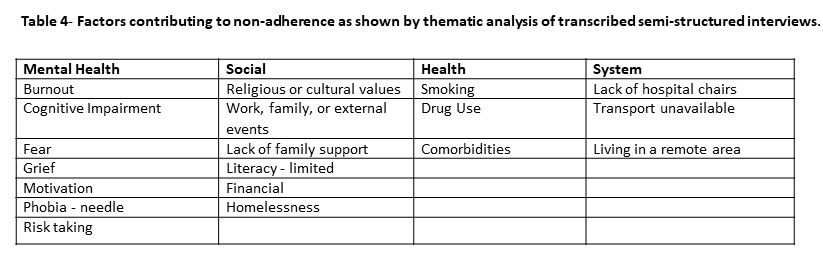

Factors identified by participants as contributing to non-adherence, and resulting in the markers discussed above, are shown in Table 4, under the subthemes of mental health, sociocultural, health and system.

Mental health concerns emerged as being manifest in many ways including burnout from undertaking treatment at home, needle phobias, grief, cognitive impairment, motivation, and fear. Evidence of these on observation or discussion with patients was reported to alert nurses that intervention was needed to support these patients maintain adherence.

Factors of a social nature contributing to non-adherence were reported as sometimes tangible and addressed before non-adherence affected physical health. Contributing social factors such as life events (holidays, birthdays, and the like) were predictable periods of non-adherence “Tends to be around events. Its not just a normal pattern, it’ll b-e, it’ll be um celebration times. It will be um, “Oh, I’ve got to get up to xxx, because you know, this is happening or that’s happening so I’ll just skip a couple of dialysis”, you know but I mean COVID um, people were pretty compliant during COVID” (Participant #4). The contrast between COVID and previous times as exemplified in the extract from Participant #4 was interpreted to mean that staying home, without competing social events, increased adherence. Non-adherence in response to transient social events was not reported by participants to be a cause for alarm. Other contributing social factors such as belief system, literacy and financial constraints were identified as modifiable if attended to. For example, financial constraints could affect the purchase of medications, water, and electricity, all of which could have an impact on adherence. One participant mentioned concern about non-adherence where electricity is pre-purchased and could run out during the night regarding use of a night dialysis machine. Another cited offering financial support for medication costs. Participants did advise that they were alert to other social factors and would intervene before biological markers were noted - in particular where financial constraints on purchasing medication “or are they non-adhering because they don’t um have money um, they can’t afford, they have to make decisions whether or not “I don’t have any money so I can’t buy the medications that I need and I have to made a decision whether or not I buy my um injections that I need to have” versus um buying this other medication or buying food. So I suppose its looking at um those sorts of things that you have to look at the bigger picture with these patients as well.” (Participant #5). Other social factors contributing to non-adherence noted by participants included a lack of family or partner support, commitments to work or family and religious or cultural practices, and homelessness.

Intervention

Participants described their clinical role to be monitoring adherence and providing support to both prevent, and intervene, when indicated. The decision about when to intervene was grounded in patient centredness, described as “Dialyse to live, not live to dialyse.” (Participant # 9).

The description provided by the nurses was of remaining in close contact with patients, knowing them well and recognising when to intervene based on individual circumstances. How and when to intervene were individually determined, reflecting both patient centeredness and the importance of the relationship between the patient and the nurse monitoring their treatment “we really do try to have an open relationship with the patients to adjust it to fit their lifestyle…. it has to be an open relationship and a trust… Some of them have mental health issues or other stressors um like financial. But we could work around them it we have that open relationship.” (Participant #3). A care philosophy was mentioned by some participants, demonstrating respect for informed individual patient choice and individualised management. Ensuring patients receive the benefits from dialysis, allowing for fulfilled lives, can have the effect that improved health itself leads to improved adherence. Compromise and meeting patients halfway were highlighted by many participants “Um, what can we do about it? I think we need to just really connect with the patient, you know, you need to understand um where they’re coming from, what they are prepared to do. And then I guess we compromise because as I said ultimately, it is their right um, and they have right um and they have a right to do their health care treatment how they want. Um and it rarely is going to be to the level that we would like to see. And patients have a right to make wrong choices. So we again try and risk mitigate um, and we mainly do that by you know offering other solutions and options.“ (Participant #6).

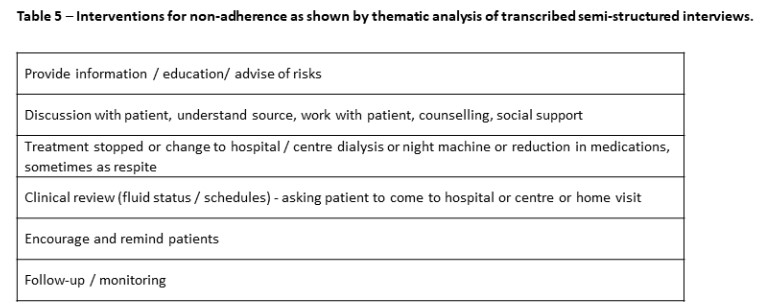

Table 5 provides a list of interventions for non-adherence identified by participants. The main theme identified in relation to intervention for non-adherence was to increase support through counselling, retraining, and providing information. In some cases, home dialysis may be stopped temporarily by offering satellite services as a break from the responsibility in a form of respite but refusing home-based dialysis as an ongoing treatment option was only offered in cases of complex co-existing medical conditions or drastic changes in circumstances.

Not all participants reported having a policy in their centres that addresses how and when to intervene for non-adherence. Documentation used in the process of supporting patients varied in relation to patient consent, documents about rights, responsibilities and management plans, governance, training sign off and missed treatments. Some policies and contracts with patients were reported to be documented, but contracts and agreements were not considered enforceable and served mostly as counselling tools.

Discussion & Conclusions

The description of the service in which each participant works provided context for the interviewer. The descriptions also yielded wide variation in non-adherence, from 0 % to 60% (or almost all patients showing some non-adherence). Variation in accounts of adherence is found in the literature [4, 22]. In our study of adherence specific to home dialysis, we gained some insight into the wide variation, in that adherence was constructed as a dynamic process. If patient adherence is a dynamic process that shifts, then variation in accounts of how common adherence (and non-adherence) is, are to be expected. Furthermore, our study has demonstrated that non-adherence to home dialysis as constructed by renal nurse practitioners is a complex entity that can emerge from both biological and behavioural markers. The findings show that nurses do allow flexibility and autonomy for home dialysis patients so that adherence is negotiated through their relationship with individual patients. Adherence is not static, nor is it the same for all patients. Classifying patients as adherent or non-adherent does not capture the complex process that constitutes living with KF. Rather, adherence is maintained or not due to an interplay of contributing factors. Thus, nurses need to continually manage potential or real non-adherence from multiple perspectives.

The findings show that at the core of constructing notions of (non)adherence are the trust and partnership between nurses and patients. That relationship is at the core of addressing adherence, as also shown by Jaquet and Trinh [23]. Central to addressing non-adherence is providing support for mental health concerns, as well as social, health and system contributing factors. Lonergan and Murali [24] conclude that addressing adherence in dialysis patients has to date mostly focused on patient related factors, with mixed results. The findings reported here support conceptualising adherence as multifaceted and potentially modifiable within the working relationship between the patient and their nurse. The participants’ descriptions of knowing their patients well offers testament to patient centredness., fitting well with patients’ accounts such as reported by Walker et al [25], that an ongoing relationship with nurses is highly valued when living with KF.

The complexity of adherence ought to be included in training and policy. The dynamic nature of adherence, and the potential for any patient to become adherent due to the emergence of contributing factors was clearly expressed by participants in this study. The potential for patients to shift between being adherent and non-adherent, as determined by multiple factors, should be further investigated, and if this is a widespread so that policies for staffing and procedures can be developed to reflect this reality.

The findings reported in this study derived from just nine participants, and so can be considered as preliminary. Although the number of participants is small, all were highly experienced specialist nurses with responsibilities for large number of patients undertaking home dialysis. The data can be generalized as these participants are representatives across each state and territory in Australia. The data, whilst derived from small numbers, was generated from lengthy in depth semi structured interviews with each of the participants. As a result, the findings offer a preliminary insight into how adherence is constructed by nurses supporting Australians undertaking home haemodialysis or home peritoneal dialysis. The findings differ markedly from the early definitions of adherence to dialysis based on hospital haemodialysis as mentioned in the introductory remarks to this paper. Instead of being defined by biological markers of disease, adherence for home dialysis patients is described here as a shifting, dynamic process grounded in relationship. Further research, built on the preliminary findings presented here, would be beneficial to both healthcare teams and to patients living with KF. As a next stage, investigating how patients’ perspectives fit with these nurses’ accounts could expand the understanding of how non-adherence and adherence occurs in the lived experienced of patients with KF.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contribution

Josephine S F CHOW: Conceptualization, methodology, data analysis, project administration, manuscript preparation

Louise COLLINGRIDGE: Data collection, methodology, formal analysis, manuscript preparation

Jacqueline RAMIREZ: Data curation, formal analysis, manuscript preparation

Janine BYRNE: Conceptualization, manuscript preparation

Allyson CALVIN: Conceptualization, manuscript preparation

Glenda RAYMENT: Conceptualization, manuscript preparation

Rosemary SIMMONDS: Conceptualization, manuscript preparation

Nadine TINSLEY: Conceptualization, manuscript preparation

All authors agreed to the submission of the manuscript for publication.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the South Western Sydney Local Health District Research and Ethics committee (Ref: 2021/ETH11095).